Is Food Poisoning the Cause of Your IBS?

Have you ever wondered: “Why has my gut never been the same after that bout of food poisoning?” If so, you’re not alone. Many people notice long term changes after an acute episode of gastroenteritis (food poisoning). You might find that your bowel patterns have shifted, you fill up much faster than you used to, or your digestion feels unpredictable from day to day. These changes are extremely common after food poisoning and research now shows that a large percentage of people develop something called post infectious IBS.

What Is IBS and How Common Is It?

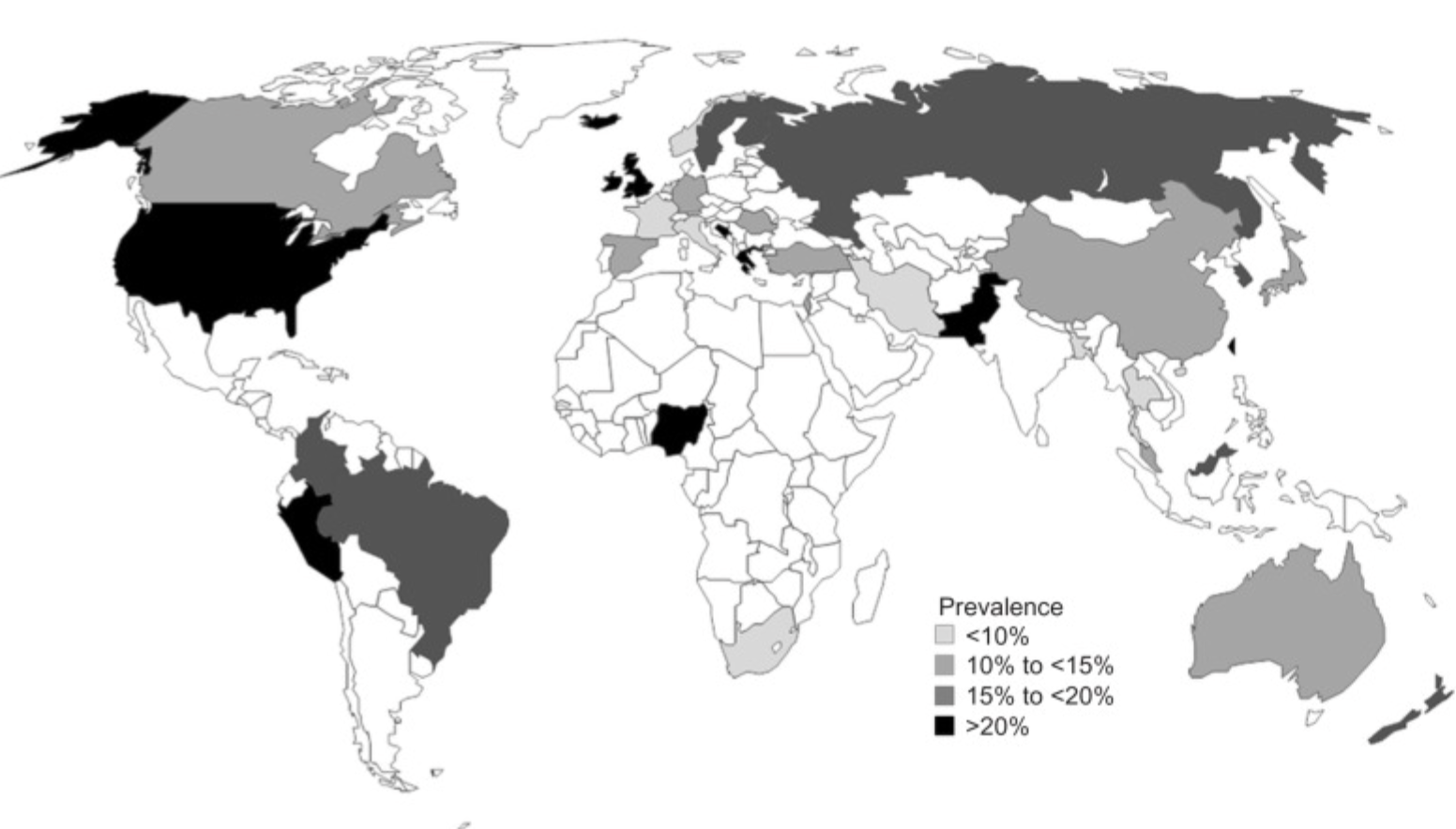

Worldwide prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome, as reported by country. Image from Canavan et al., 2014

IBS stands for Irritable Bowel Syndrome, a functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder that affects how your gut works, not because of structural damage, but due to problems with motility, nerves, and sometimes immunity. In IBS, you typically experience recurrent abdominal pain associated with changes in bowel habits such as diarrhea, constipation, or a mix of both.

Making the diagnosis of IBS often requires Rome criteria (currently Rome IV), which define IBS as symptoms like abdominal pain or discomfort present at least 1 day per week in the last 3 months, with onset at least 6 months before diagnosis, plus a change in stool frequency or form. It also requires ruling out other causes.

As for prevalence: according to a large U.S. survey using Rome IV criteria, about 6.1% of U.S. adults meet the diagnostic criteria for IBS. Globally, estimates vary; many sources suggest 10–20% of the population may have IBS. Women are significantly more affected than men; in many studies, about two-thirds of people with IBS are female.

The After-Effects of Food Poisoning: Why Your Gut Might Never Be the Same

If you’ve had a bad case of food poisoning in the past, there’s a real possibility that your gut was altered in a lasting way. Research shows that about 25% of people who suffer acute gastroenteritis go on to develop a form of IBS called post-infectious IBS (PI-IBS).

Dr. Mark Pimentel and colleagues have found that up to 70% of people who develop IBS may have had a prior gastrointestinal infection, suggesting a strong link between food poisoning and long-term gut dysfunction. While this number can vary depending on the population and study, PI-IBS is now widely accepted as a major subtype of IBS.

The Biology Behind It: Cytolethal Distending Toxin B, Vinculin, and Autoimmunity

So, what exactly happens in the body after food poisoning to trigger IBS? Here is a breakdown of the proposed mechanism:

Toxin Production by Pathogens

Some food-borne, gram-negative bacteria (for example, Campylobacter, Salmonella, E. coli, or Shigella) release a toxin called cytolethal distending toxin B (CdtB) during infection.Immune Response & Antibodies

Your immune system makes antibodies to CdtB as it fights the infection (this is normal and a good response).Molecular Mimicry with Vinculin

Here’s where things get tricky: vinculin is a protein in the body expressed in the intestinal cells, including the cells that help coordinate gut movement and structure. Studies suggest that anti-CdtB antibodies sometimes mistakenly attack vinculin, because parts of the toxin look like (mimic) parts of vinculin. When this happens, we get anti-vinculin antibodies.Damage to Gut Motility Mechanisms

Vinculin is part of the cellular machinery in the gut, including structures that help nerve cells and muscle cells in your intestines communicate. When vinculin is disrupted, it can impair something called the migrating motor complex (MMC), a pattern of muscular contractions in your small intestine that helps clean out leftover food, bacteria, and debris between meals (sort of like intestinal housekeeping).SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth) and Motility Issues

These antibodies have been linked to being a root cause of SIBO as they can damage the way the small bowel is able to contract. Studies suggest this may also be part of delayed gastric emptying or gastroparesis, where food stays in your stomach and small intestine longer than it should. You might feel full quickly, experience bloating, or notice that your symptoms worsen as the day goes on.

Why Does This Happen to Some People and Not Others?

Not everyone who gets food poisoning ends up with IBS; why?

Some people may have enough stomach acid (hydrochloric acid) to kill the bacteria before they produce enough toxin needed to cause this reaction.

Others may have fast, efficient motility, so the toxins and bacterial byproducts don’t linger.

Preexisting conditions matter: stress, dysbiosis, or even slight gut motility issues may make someone more vulnerable to developing antibodies and sustaining damage.

On the other hand, people with a healthy gut, balanced microbiome, and good immune regulation may recover fully without long-term consequences.

Testing for This Mechanism in Clinical Practice

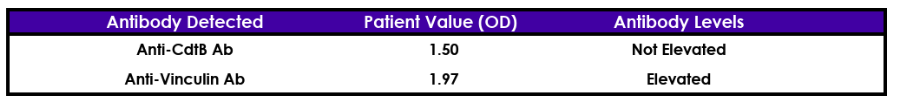

As a functional gastroenterologist, one of the most powerful tools I use is antibody testing:

We look for anti-CdtB antibodies (to detect prior toxin exposure)

We also test for anti-vinculin antibodies (to see if there is autoimmune-type attack on the gut)

These biomarkers are strongly associated with post-infectious IBS. To test for this, I use either IBS Smart (as pictured above) or a specialized IBS / Candida panel from Vibrant Wellness that includes tests for these antibodies. Knowing whether these antibodies are present can be a game-changer because it points to a root cause, not just symptom management.

Why This Diagnosis Matters

Many times, people are labeled with “IBS” simply because doctors are not sure what else to call their symptoms. But if your IBS is post-infectious and immune-mediated, the treatment is different. Instead of just managing pain or bowel habits, we can aim to:

Support optimization of the migrating motor complex

Improve motility

Rebalance the gut microbiome

This root-cause approach offers a real path to healing, instead of merely managing symptoms.

Is This You?

If you have been living with IBS symptoms for years without a clear explanation, try to think back and remember if these changes started after a bout of food poisoning. Oftentimes, people recover from the acute illness but these troublesome symptoms develop weeks later and they don’t realize that food poisoning was the trigger. Antibody testing (for CdtB and vinculin) may provide clarity about what is actually going on in your gut.

Next Steps: How to Get Help

If this resonates with you, here’s how we can help:

Schedule a functional GI consultation to review your history, symptoms, and labs.

Ask about the Candida/IBS panel to assess whether you're dealing with post-infectious IBS.

We will build a personalized treatment plan to heal motility, support your immune system, and rebalance your gut.

The good news is that healing from years of GI distress is absolutely possible, especially when you treat the root cause, not just the symptoms.

Important Caveats

Not all IBS is caused by food poisoning. IBS is a diverse syndrome with many potential triggers (diet, stress, SIBO, dysbiosis, hormones, etc.).

Even if antibodies are not elevated, you may still benefit from a functional GI approach.

Antibody testing is only one piece of the puzzle; it should be combined with clinical history, motility testing, stool & microbiome assessment, and other labs as needed.

Conclusion

Food poisoning is not just an acute inconvenience; for some people, it changes the gut forever. When gram-negative bacteria produce CdtB, our bodies may mount an immune response that inadvertently attacks our own vinculin protein, disrupting gut motility and leading to post-infectious IBS. If your IBS began after an infection, or if traditional symptom management isn’t working, consider antibody testing. Identifying this root cause can unlock more precise, effective, and long-lasting healing.

If that sounds like you, we would be honored to walk with you on your journey back to gut health. Schedule an appointment today.

References

Almario, Christopher V et al. “Prevalence and Burden of Illness of Rome IV Irritable Bowel Syndrome in the United States: Results From a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study.” Gastroenterology vol. 165,6 (2023): 1475-1487. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2023.08.010

Borghini F, Donato G, Alvaro D, Picarelli A. New insights in IBS-like disorders: Pandora's box has been opened; a review. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2017; 10(2): 79-89.

Canavan, Caroline et al. “The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome.” Clinical epidemiology vol. 6 71-80. 4 Feb. 2014, doi:10.2147/CLEP.S40245

Zaki, Maysaa El Sayed et al. “Study of Antibodies to Cytolethal Distending Toxin B (CdtB) and Antibodies to Vinculin in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome.” F1000Research vol. 10 303. 19 Apr. 2021, doi:10.12688/f1000research.52086.4